Satellite Data Tracking And Machine Learning

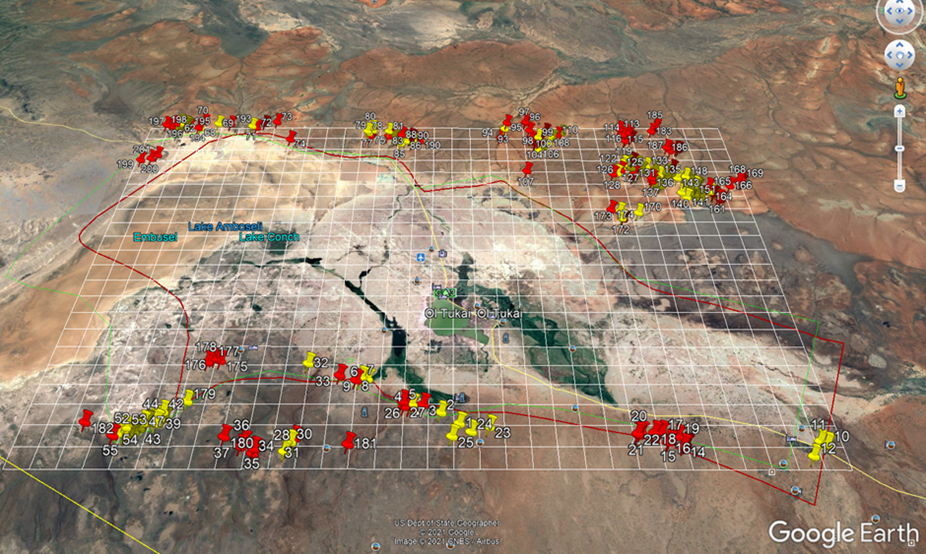

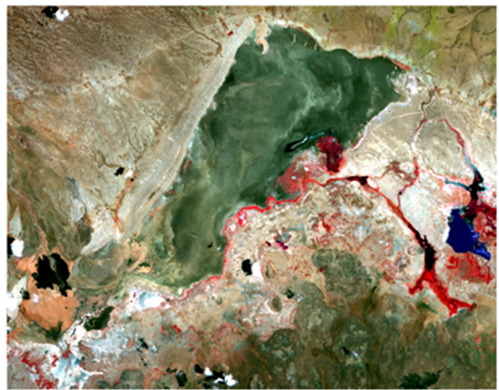

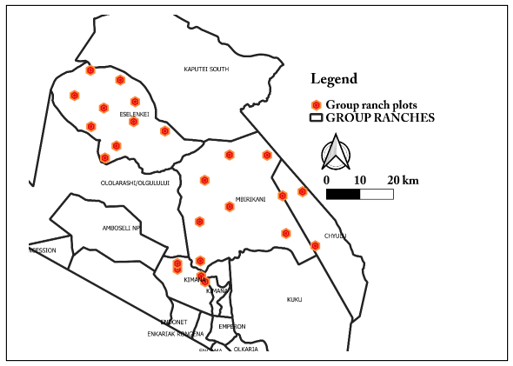

In the recent times, ACP has adopted satellite data processing and analysis for the Amboseli Ecosystem using remote sensing techniques to analyse spatial trends of various data sets including settlements and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) within grids and plots.

Remote sensing is a technique to observe the earth surface or the atmosphere from out of space using satellites (space borne) or from the air using aircrafts (airborne).

The full list of data obtained by ACP from satellite products such as Google Earth Engine (GEE) includes, NDVI, rainfall, temperature, altitude, tree height and soil types. (Figure 15)

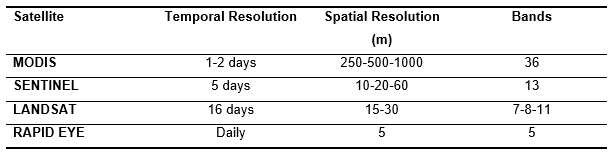

The satellite data on rainfall does complement the raingauge measurements at the Kenya Wildlife Service Headquaters weather station in Amboseli. (Table 4)

Machine Learning Application

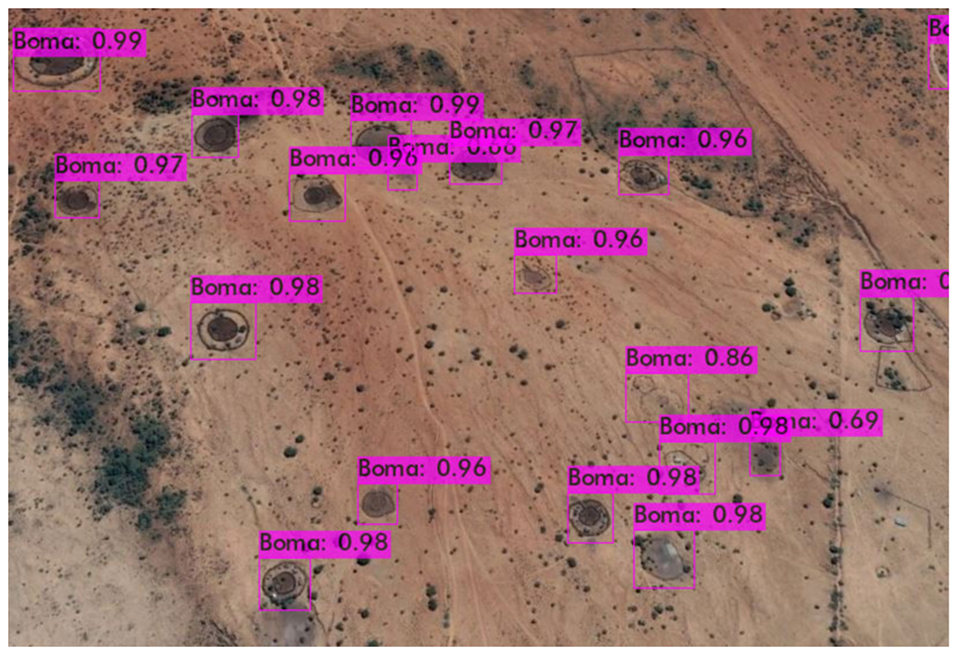

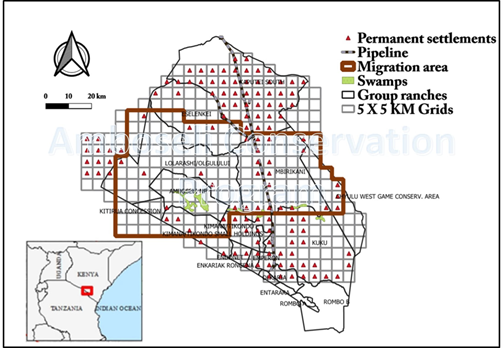

ACP has also recently started the use convolutional neural network (CNN), a specialized type of artificial neural network (ANN) to detect human settlements (bomas) from satellite images in Amboseli. (Figure 16)

CNN and ANN are machine learning techniques for computer vision using yolov4 model. All of the YOLO models are object detection models. Object detection models are trained to look at an image and search for a subset of object classes.

When found, these object classes are enclosed in a bounding box and their class is identified. Object detection models are typically trained and evaluated on the COCO dataset which contains a broad range of 80 object classes. From there, it is assumed that object detection models will generalize to new object detection tasks if they are exposed to new training data.

ACP will continue improving on the machine learning algorithm, working with experts and partners, to obtain accurate predictions and expand the area of study to cover the surrounding ecosystems.

Satellite Image Processing

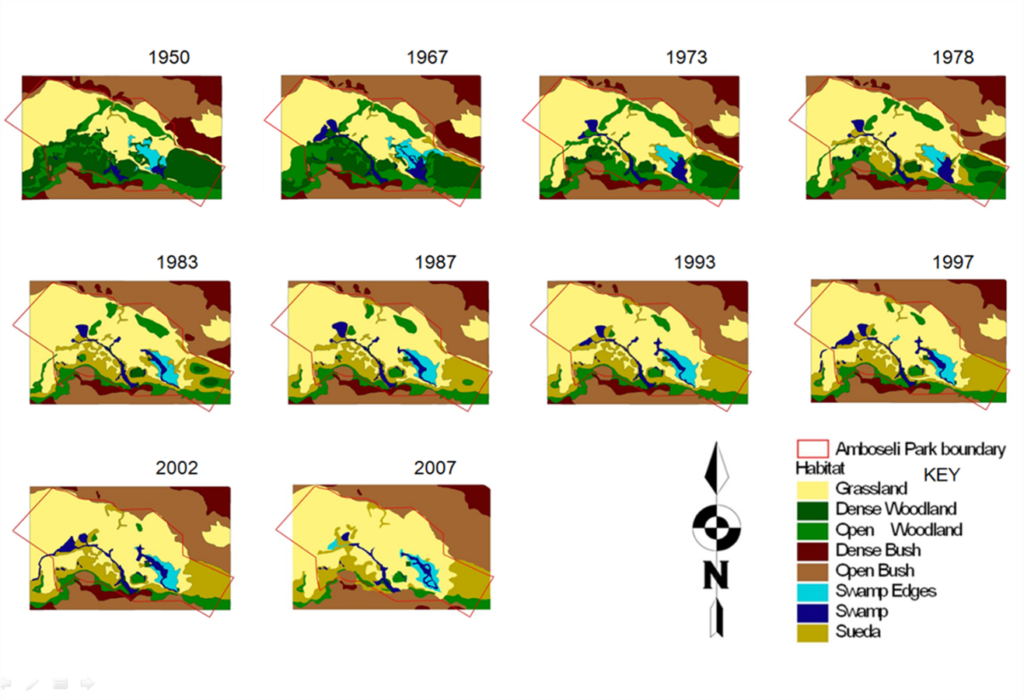

The Amboseli conservation program also processes satellite imagery to complement aerial photography for the purposes of detecting more than half a century habitat changes (Figure 17) in the basin area.

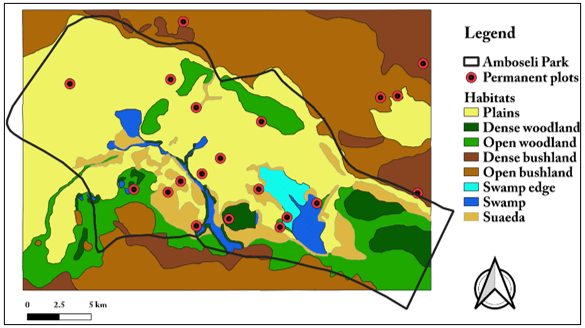

The changes in habitats and vegetation are updated every five to ten years from 1950 when the first aerial photograph was taken (Figure 18). The recent updated basin vegetation map is based on a supervised classification of satellite imagery from Sentinel 2.

Satellite Data Tracking And Machine Learning

In the recent times, ACP has adopted satellite data processing and analysis for the Amboseli Ecosystem using remote sensing techniques to analyse spatial trends of various data sets including settlements and NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) within grids and plots.

Remote sensing is a technique to observe the earth surface or the atmosphere from out of space using satellites (space borne) or from the air using aircrafts (airborne).

The full list of data obtained by ACP from satellite products such as Google Earth Engine (GEE) includes, NDVI, rainfall, temperature, altitude, tree height and soil types. (Figure 15)

The satellite data on rainfall does complement the raingauge measurements at the Kenya Wildlife Service Headquaters weather station in Amboseli. (Table 4)

Machine Learning Application

ACP has also recently started the use convolutional neural network (CNN), a specialized type of artificial neural network (ANN) to detect human settlements (bomas) from satellite images in Amboseli. (Figure 16)

CNN and ANN are machine learning techniques for computer vision using yolov4 model. All of the YOLO models are object detection models. Object detection models are trained to look at an image and search for a subset of object classes.

When found, these object classes are enclosed in a bounding box and their class is identified. Object detection models are typically trained and evaluated on the COCO dataset which contains a broad range of 80 object classes. From there, it is assumed that object detection models will generalize to new object detection tasks if they are exposed to new training data.

ACP will continue improving on the machine learning algorithm, working with experts and partners, to obtain accurate predictions and expand the area of study to cover the surrounding ecosystems.

Satellite Image Processing

The Amboseli conservation program also processes satellite imagery to complement aerial photography for the purposes of detecting more than half a century habitat changes (Figure 17) in the basin area.

The changes in habitats and vegetation are updated every five to ten years from 1950 when the first aerial photograph was taken (Figure 18). The recent updated basin vegetation map is based on a supervised classification of satellite imagery from Sentinel 2.