Ecosystem News

Bucking the dismal decline in wildlife: Amboseli numbers are going up

Bucking the dismal decline in wildlife: Amboseli numbers are going up

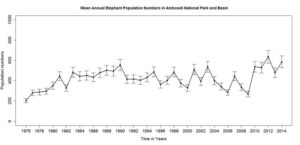

Amboseli Conservation Program’s five decades of continuous monitoring the Amboseli region shows an astonishing turnaround for wildlife after years of decline. Many species are now more abundant than forty-five years ago, a remarkable contrast to the rapid losses across Africa and around the world.

What explains this small point of light in a gloomy outlook for wildlife? What lessons does Amboseli offer conservation? And how can the success be kept up as the space for wildlife shrinks?

As scientists patch together wildlife counts of the past few decades, a dismal picture emerges. Joseph Ogutu and associates (2016) show wildlife to have declined by over two thirds in Kenya since the late 1970s. Western and colleagues found similar declines in protected areas (Western et al., 2009), and yet other biologists show numbers to have fallen by well over a half across Africa (Caro and Scholte, 2007; Craigie et al., 2010).

Africa’s wildlife losses mirror worldwide trends. The World Wildlife Fund’s distillation of 14,000 populations of 3,700 species of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians, and reptiles have slumped by nearly sixty percent in forty years (WWF 2016). The causes? Over-harvesting, land and habitat loss, ecosystem degradation and climate change.

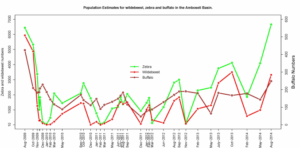

In our ACP counts of the eastern Kajiado’s former pastoral lands north and south of Amboseli we find the same picture. Here, where migratory populations of wildebeest, zebra, elephants, giraffe and eland spread from the slopes of Kilimanjaro to the Mombasa Road in the early 1970s, the herds have all but vanished. Amboseli stands alone as the only ecosystem in Kenya to have sustained its wildlife numbers since the 1970s. More remarkably, the numbers of two threatened species, the elephant and giraffe, have grown.

Let’s take a closer look at the Amboseli record and the cause of its conservation success.

The causes of wildlife declines in eastern Kajiado as in Kenya generally include population growth, land pressures, sedentarization, pasture degradation, poaching, human-wildlife conflict, and drought (Western et al. 2009a, Ogutu et al. 2014, Okello et al. 2016). Of the many threats, by far the gravest is subdivision and settlement.

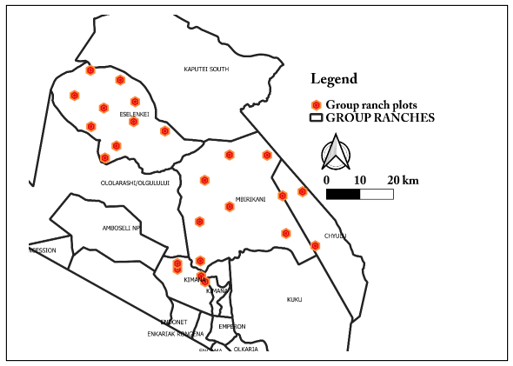

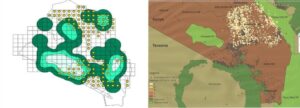

The impact of privatization and burgeoning permanent settlements on wildlife in the formerly open pastoral lands is well documented after the subdivision of the Kaputei Group Ranches north of Amboseli. Here, wildlife declined sharply from 1970 to 2005 following land subdivision (Western et al. 2009a). In stark contrast, wildlife increased on the adjacent open lands of Mbirikani Group Ranch (see figure below). The losses on the privatized Kaputei ranches arose from displacement by closely spaced settlements and pasture losses due to heavy year-round grazing (Groom and Western 2013). Aerial counts we’ve conducted since 2005 show wildlife declining faster still on Kaputei and Mbirikani rebounding strongly after the severe drought of 2009.

The future of Nairobi National Park: a review of the 2022-2030 plan

The future of Nairobi National Park: a review of the 2022-2030 plan

The Kenya Wildlife Service has floated a ten-year plan (2020-2030) for Nairobi National Park. This is timely and urgently needed. Nairobi was Kenya’s first national park, gazetted in 1946. With the park under growing pressure on all sides, and from within, its future looks bleak as the standard bearer of Kenya’s parks.

The Kenya Wildlife Service has floated a ten-year plan (2020-2030) for Nairobi National Park. This is timely and urgently needed. Nairobi was Kenya’s first national park, gazetted in 1946. With the park under growing pressure on all sides, and from within, its future looks bleak as the standard bearer of Kenya’s parks.

What better event to celebrate the 75th anniversary of our national park than a plan to secure the future of Nairobi National Park for all time? The ten-year plan to save and restore the park is five years late and doubly urgent because of the delay.

Unfortunately, KWS was put under pressure to ram through the proposal with little public input apart from box-ticking. The railroading ran up against a hail of criticism. Hidden from view were a rash of developments that run counter to the goals of the Wildlife Act 2013: to keep parks in an “untrammeled” natural state.

With KWS already having ceded parts of the park to the Southern Bypass Road, overhead rail line and a goods depot in the works, the public criticisms are well grounded.

I participated in public reviews of the Nairobi National Park 2020-2030 plan and have given my comments at various meetings and to KWS directly. I feel strongly that the plan needs all the public participation it can get and will be greatly strengthened by the input and guidance. Kenya’s parks are, after all, vested in the citizens of Kenya, not the government.

KWS as the custodian has the heavy burden and deep responsibility to ensure its future for all its peoples, and as a world heritage. I was asked by Swara magazine to review the plan. The review is given here. Most of the points are straightforward, but I had too little space to expand on the two most important points of all: fencing and the ecological restoration of the park. I have added some addition points here to clarify my views and recommendations.

I visited NNP regularly in the late 1960s when I was a graduate student at the University of Nairobi starting out on my research and conservation work in Amboseli. The park in the early dry season was like a mini-Serengeti with long lines of zebra and wildebeest snaking back into the park from their wet season migrations on the Athi Plains.

During the rains, large resident herds of kongoni, impala, warthog, gazelle and solitary territorial wildebeest dotted the short grass plains, giving lions and cheetahs abundant prey to keep them in the park. In the early 1970s, as I flew across the Athi Plains to Amboseli, I looked down on the tens of thousands of wildebeest and zebra stretching across the southern plains from Konza to the rift edge during the rains. Traffic on the Namanga Road was often held up for minutes by the migrating herds.

In the early 1980s when I bought land bordering the park, I wandered across the open plains, stretching unbroken to Kajiado, through large herds of eland, wildebeest and zebra, all milling about waiting to file across a narrow defile in the Mbagathi gorge into the park. Within a few years the wildebeest migrations were severed by residential housing.

A solitary male hung on in a resident herd of impala on our land for a further year before he too disappeared. By then the tens of thousands of migratory animals on the Athi Plains had been whittled down by meat poachers, sprawling settlements and fences to a whisper of their former honking masses.

Once the migratory herds dwindled, long grasses and shrubs spang up with the falling grazing pressure and the suspension of burn management programs the wardens formerly used to prevent the invasion of rank vegetation. By the late 1980s, when it was clear that wildebeest were shunning the tall rank grasses in favor of the shorter grasslands on the Athi ranches to the south, I asked Helen Gichohi, a MS student at the time, to conduct an experimental burning program to restore the shorter grasslands.

Her study showed how early burning to create shorter greener grasses became a magnate for wildebeest, zebra, gazelle and warthog, as they were in the 1960s (Gichohi, 1990). We went on to show that the more heavily grazed grasses outside the park were richer and more palatable than the rank grasslands inside. In other words, parks can lose their richness of wildlife and vegetation without restorative management (Western and Gichohi, 1994).

In the mid-1990s, as director of the Kenya Wildlife Service, I used the evidence of Helen’s work to begin restoring the dwindling wildlife numbers and grasslands using an experimental early burning program. The results were dramatic. For the next three years the burned area in the south west of the park drew in large herds of wildlife and an entourage of visitors.

After I left KWS, conservation lobbyists pressured KWS to abandon the restoration program, arguing nature should be left unmanaged. The heavy El Niño rains of 1998 hastened the growth of tall vegetation and the decline of wildlife, especially the smaller species, including gazelles and warthogs.

The dwindling herds of wildebeest and zebra returned to the park later each season and, the once resident herds in the rain season shrank too, lions and cheetahs began regularly attacking livestock outside the park.

By 2010 dense settlements spreading out from Ongata Rongai township and Tuala blocked all wildlife movements at the western end of the park. I saw the last cheetah shortly afterwards and worried about the mounting toll of lion and hyena attacks on livestock and dogs in the residential estates.

The community, angry and scared, demanded KWS remove the predators and fence the park after a series night encounters. In December, the anger bubbled over when a person returning from Tuala late at night was eaten by a lion.

I’m no fan of fencing parks. I’ve done all I can to prevent that happening by promoting community-based conservation and nature enterprises as a win for park neighbors and wildlife. The 150-plus conservancies in Kenya testify to the success—where land is still open. Where parks are surrounded by a sea of settlement, the Aberdare, Shimba and Nakuru among them, fences are vital for protecting wildlife and people.

I’ve promoted fencing in each of these cases and raised funds to electrify the fence hard up against the city on its northern and western boundaries. Yet I hold out the hope of avoiding fencing the park on its southern border.

How in any event would the park be fenced when the center of the Mbagathi River is the park boundary? The only option is to fence inside the river edge, but this would exclude the river, the park’s most important lifeline. There are other problems with fencing in the southern park.

Unless the grasslands and wildlife are restored first, the park will become more of an ecological trap than conservation lifeline as predators drive down the depleted herds even further. The herbivores need as much space and movement as possible to sustain the interplay of predators, prey and healthy pastures.

Adding to the fencing problem, not all residents south of the park agree on the solutions. The Ongata Rongai and Tuala residents want the park fenced now, and there is no other option. The eastern end of the park remains open though, and the largely Maasai ranching community has joined a leasing program to keep wildlife on their lands, hoping to benefit from nature enterprises. Many oppose fencing altogether.

I’ve long advocated that the debate about whether to fence or not should be informed by what is to be fenced in and left out. Even if the park is to be fenced in, the abundance and diversity of plants and animals should be restored first to avoid further ecological decline. KWS is to be commended for making ecological restoration a primary plant of the 2020-2030 Plan.

The restoration program stands to boost wildlife numbers, keep predators anchored in the park, improve habitat quality and diversity, and raise the park’s profile and visitor appeal. I’ve suggested in the Swara article that the southern fence be considered in three phases, emulating the step-by-step approach to fencing in the Aberdare National Park.

For Phase 1, I’ve joined neighboring landowners along the Mbagathi River discussing with KWS a fence running along the back of our properties as far as Maasai Gate. This will give wildlife access to the river and use of our land and prevent predators from straying into the built-up Ongata Rongai and Tuala areas.

Phase 2, running from Maasai Gate to the overhead rail line, needs similar consultations to see how far into the Athi Plains the fence can extend.

Phase 3, from the rail line to the eastern border of the park, is far more contentions. Here most landowners are Maasai ranchers who have formed a wildlife conservancy and land leasing arrangements, hoping to benefit from wildlife on their land.

The prospects for winning a large area of open space for wildlife are good yet call for detailed property and land surveys and open discussions. This will take time. Rushing ahead without due process will anger the community, frustrate KWS and short-change wildlife.

KWS should focus on getting agreement on the broad principles and strategies in the 2020-2030 plan for Nairobi National Park and work out the details as a part of its execution. As the plan stands, it is too saturated with details.

It loses sight of the broad areas of agreement, public support and continuing engagement and refinement needed for the plan to succeed. No two issues in the plan need these open-minded flexible approaches more than ecological restoration and fencing.

Gichohi, H. W. (1990). The Effects of Fire and Grazing on the Grasslands of Nairobi National Park. MSc thesis. University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya.

Western, D. and Gichohi, H. (1994). Segregation effects and the impoverishment of savanna parks: the case for an ecosystem viability analysis. African Journal of Ecology 31 (4): 269-281.

Saving wildlife in a time of coronavirus : the greatest risk to human health around the world since the Spanish flu of 1918

Saving wildlife in a time of coronavirus : the greatest risk to human health around the world since the Spanish flu of 1918

The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries.

The pandemic is already disrupting every sector of society, from entertainment and sports to manufacturing and the health and service industries.

And the worst is yet to come. Conservationists blame the pandemic on the loss of biodiversity degraded ecosystems and climate change.

They have a point. New virulent diseases, along with invasive species and pests, thrive when nature dies. In the case of the Coronavirus the blame lies squarely on the illegal trade in wildlife species, fueled by globalization.

Diseases such as Ebola, Marburg and HIV erupted in small scattered communities in the past but remained localized epidemics. No longer.

In the last few decades, global travel has spawned virulent novel viruses such as SARS, MERS, H1N1 and COVID-19, infecting hundreds of millions around the world in weeks. These new pandemics are a grave threat to every nation, every individual. causing 6 of 10 infectious diseases, 2.5 billion illnesses and 2.7 million deaths each year.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia.

The wildlife trade, worth $23 billion annually, operates largely underground like drug trafficking. And like the ivory wars which slashed elephant numbers across Africa from 1.2 million in 1970 to 450,000 today, the wildlife trade is driven by rising wealth in Asia.

Hundreds of species of amphibians, snakes, fish, birds and mammals are butchered for the wildlife trade, among them bats, civets and pangolins suspected of transmitting lethal viruses.

We can’t be sure which species in the wildlife market in Wuhan sparked the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, the cramped confined conditions flouting concerns for animal welfare and human health, have unleashed the most devastating pandemic in modern times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been dubbed the revenge of wildlife. Revenge it isn’t. Coronavirus smites indiscriminately. For every illegal trader infected, hundreds of millions of people are at risk, among them ardent animal lovers, doctors and nurses. Overlooked is the impact of the pandemic on wildlife.

Here’s why, and what you can do about it

The unseen victims of the tourism collapse are the very communities which protect and benefit from wildlife.

The unseen victims of the tourism collapse are the very communities which protect and benefit from wildlife.Amboseli, which pioneered community-based conservation in the 1970s, speaks to its success

Even the giraffe, newly listed as a threatened species, has increased in the last two decades and is among the largest and safest population in Africa. The remarkable success of Amboseli depends on the hundreds of community rangers protecting wildlife, and on the income from tourism which generates jobs, scholarships for children and supports social services and women’s enterprises. Visit here to learn more.

Even the giraffe, newly listed as a threatened species, has increased in the last two decades and is among the largest and safest population in Africa. The remarkable success of Amboseli depends on the hundreds of community rangers protecting wildlife, and on the income from tourism which generates jobs, scholarships for children and supports social services and women’s enterprises. Visit here to learn more. The South Rift Association of Landowners joining Amboseli to Maasai Mara has shown similar success. The migratory herds and lion numbers have increased, and elephants have returned to the area for the first time in decades.

The South Rift Association of Landowners joining Amboseli to Maasai Mara has shown similar success. The migratory herds and lion numbers have increased, and elephants have returned to the area for the first time in decades.Amboseli Ecosystem Count February 2020

Amboseli Ecosystem Count February 2020

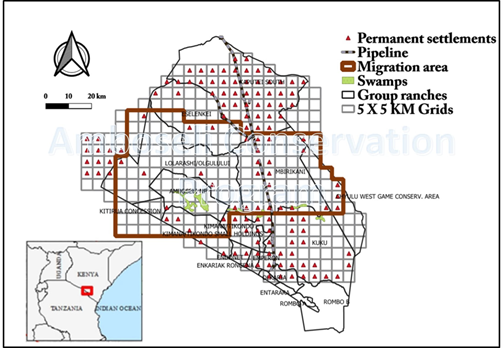

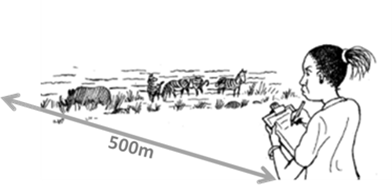

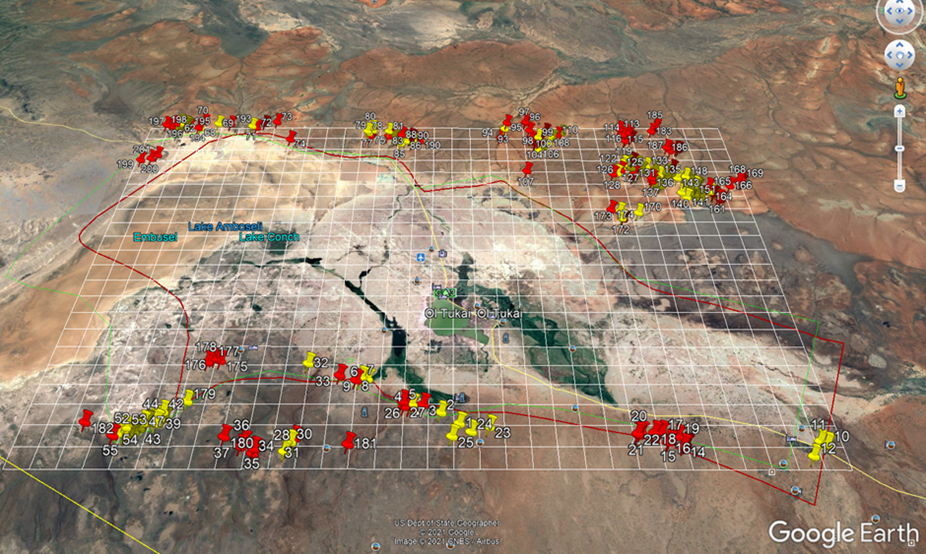

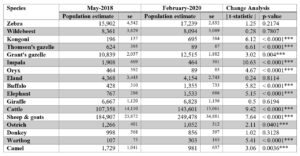

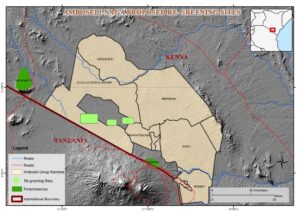

ACP commissioned the Department of Resource Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS) to conduct an aerial count of the Amboseli ecosystem and surrounding areas in February. The sample count covered approximately 7800 km² of Eastern Kajiado between February 10th and February 14th, 2020.

ACP commissioned the Department of Resource Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS) to conduct an aerial count of the Amboseli ecosystem and surrounding areas in February. The sample count covered approximately 7800 km² of Eastern Kajiado between February 10th and February 14th, 2020.

The methodology followed the same procedures and covered the same areas as counts conducted regularly by ACP since 1974.

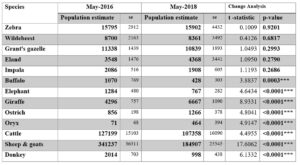

The results of the February count are given in the table below, followed by the distribution maps for each species.

The counts and standard errors for each species are given in the table alongside figures for the 2018 count to compare changes in population size.

We draw several conclusions and observations from a comparison of the 2018 and 2020 counts.

We draw several conclusions and observations from a comparison of the 2018 and 2020 counts.

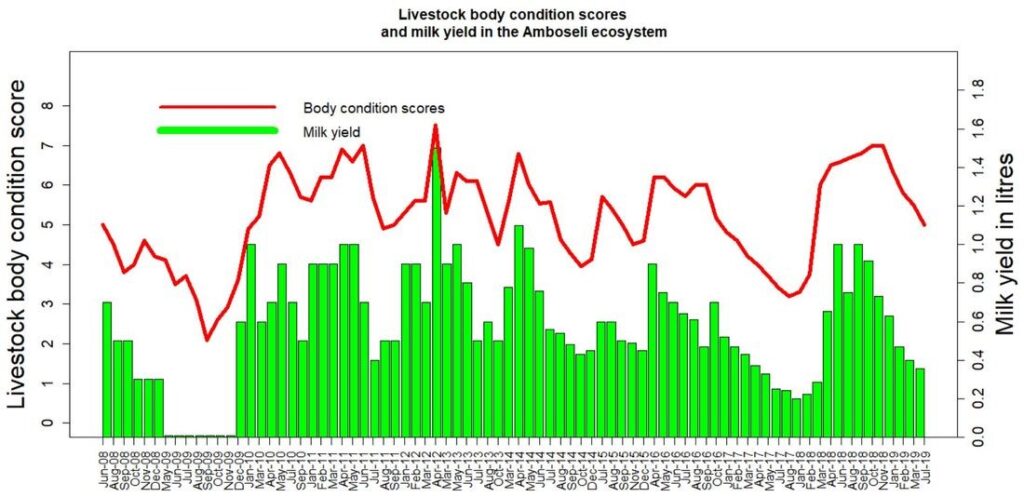

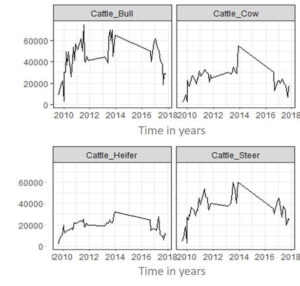

There have been significant increases in cattle, sheep and goats, despite the declining trends until 2018 and a sharp fall in body condition and milk yields in cattle over the past two years, as indicated by our pressure gauge index.

The indications are that the higher numbers reflect livestock returning to the Amboseli ecosystem following widespread movements in search of forage during May of 2018 when the count was conducted. A similar case can be made for elephant numbers. During the dry spell of 2018, many elephants moved out of the Amboseli region in search of forage.

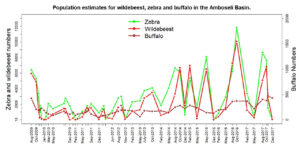

Increases in kongoni and warthog numbers may reflect the increased likelihood of being detected during wet rather than dry seasons. The increase in buffalo numbers may reflect the statistical quirk of hitting or missing small clustered herds in the Amboseli basin where monthly total counts record a population of 400 or so.

The increase in Grants gazelle likely continues the upward trend in population over the past decade. The population sizes of Thomson’s gazelle, impala, oryx, ostrich and camel are small, the standard errors large, and so the reliability of detecting actual changes over a two-year very low. ACP is currently completing a detailed analysis of the long-term trends of all species in the ecosystem to amplify the changes and causes.

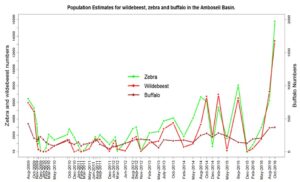

Perhaps the most reassuring figures in the 2020 count are for zebra, wildebeest, eland and giraffe, the most abundance of the wildlife species. The zebra population is evidently continuing its upward trend since the severe drought of 2009 and is close to the highest peak recorded since 1974.

Wildebeest, eland and giraffe populations all held stable over the past two years despite the declining pasture conditions in 2019. The giraffe result is especially gratifying. At over 6,500, the Amboseli giraffe population is among the largest in Africa and defies the rapid declines recorded across its range in the past few decades.

The long rains in April and May of 2018 were exceptionally heavy and replenished pastures across the region. However, the heavy stocking rates quickly depleted the recovery and set in motion another decline in pasture production throughout 2019 when young livestock began to die.

The torrential short rains which began in September 2019 and continued through to March 2020 have changed what was shaping up to be a severe year. The prolonged rains have pushed pasture production to a peak reached in the El Niño year of 1998. The replenished pastures provided a temporary stay on the steady decline in pasture production recorded since 2016 and will likely see a stepped recruitment in livestock and wildlife populations in the coming year.

Unless, however, there is a reduction in the heavy persistent grazing pressure caused by the current large livestock populations, the pasture restoration seen in increased ground cover and forage production will revert to a downward trend by the end of 2020.

Livestock and their management are key to the future of Africa’s wildlife

Livestock and their management are key to the future of Africa’s wildlife

Protected areas have committed over 15 percent of Earth’s lands to the conservation of wildlife. But these are too small and isolated to protect most biodiversity or curtail species losses. In recent decades recognition of these limitations has spurred new ways to buffer parks and safeguard biodiversity by conserving wildlife in human-dominated landscapes.

Protected areas have committed over 15 percent of Earth’s lands to the conservation of wildlife. But these are too small and isolated to protect most biodiversity or curtail species losses. In recent decades recognition of these limitations has spurred new ways to buffer parks and safeguard biodiversity by conserving wildlife in human-dominated landscapes.

Moving beyond protected areas calls for realigning conservation paradigms to ensure the lives of rural people are improved and their lands conserved.

In our Review & Synthesis article published in People and Nature, we use a case study from the rangelands of Southern Kenya, to explore how large migratory herds of wildlife which have coexisted with pastoralists for millennia can be sustained by fusing traditional husbandry practices with contemporary governance institutions and conservation policies.

We show how herding families, using the traditional notion of erematare which links the welfare of the family to the productivity of the herd sustained by free-ranging movements across large open landscapes, indirectly conserve wildlife. The value of wildlife as second cattle during droughts is captured by the Maasai saying: “we protected wildlife from hunters, and wildlife protected us from drought. Coexistence is the essence of survival for us both.”

The erematare linkages between the family, their herds, and their mobility in response to forage availability, disease and other hazards, maximize livestock productivity, minimizes drought exposure and facilitates the coexistence with wildlife. The large open landscapes which underlie the success of pastoral economies are intimately linked to an extensive network of associates and governance procedures among herders based on social reciprocity.

The large open landscapes sustaining pastoral herds and wildlife and their coexistence are facing increases threats across the savannas from land subdivision, sedentarization of herders, and rangeland degradation. We show that the traditional social and ecological linkages embodied in erematare incorporated into contemporary institutions and collective governance procedures can sustain large open landscapes and, in the process, conserve wildlife, pasture, water and natural habitats.

The large open landscapes sustaining pastoral herds and wildlife and their coexistence are facing increases threats across the savannas from land subdivision, sedentarization of herders, and rangeland degradation. We show that the traditional social and ecological linkages embodied in erematare incorporated into contemporary institutions and collective governance procedures can sustain large open landscapes and, in the process, conserve wildlife, pasture, water and natural habitats.

We show that an emerging blend of traditional and contemporary governance institutions can improve family income through livestock and range management and wildlife enterprises. The creation of landowners’ associations focusing on livestock and linked across the landscape to secure mobility, in the face of subdivision and alienation, indirectly conserve regional biodiversity, and the large free-ranging herbivore and carnivore populations support the economy of the region.

The large open landscapes and conservation of habitats also sustains ecosystem functions and services. The “inside-out” approach we highlight reverses the top-down outside interventionist approaches that have typified wildlife protection.

Based on self-interest in improving livelihoods, securing access to large open landscapes and diversifying incomes through wildlife enterprises and natural capital, the inside-out approach has the potential to buffer protected areas and open up large additional landscapes for wildlife in the rangelands, indigenous forest management, and marine fisheries.

Extreme flooding in Amboseli National Park

Extreme flooding in Amboseli National Park

Background to the floods

Background to the floods

The heavy rains in Kenya which began in September and continued through January caused extreme flooding in Amboseli National Park.

By December the floods stretched from the Loitokitok to Namanga roads (see photos below) causing a closure of the airfield and viewing roads. Inbound air traffic was diverted to Tawi and Ol Doinyo Uas strips, resulting in transfer times to the lodges of up to three hours.

The disruptions and tourist complaints carried in the social media led to cancellations and heavy revenue losses to the hotels and the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS).

The lodges, led by Ol Tukai, called for a meeting in Amboseli on 18th January to see what could be done to open the airstrip, roads and solve the flooding problem. The meeting was chaired by the senior warden of Amboseli, Kenneth Nashu, and attended by KWS road engineers, Ol Tukai Serena and Ol Tukai lodge representatives, Amboseli Trust for Elephants and the Amboseli Conservation Program.

The warden noted that the flooding had grown worse in recent years, was causing extensive damage to the roads and threatened the future of tourism in the park. He asked the meeting to identify the source and cause of the flooding, restorative measures for the airfield and roads, and preventive measures to curb future floods. The lodge operators, raising their concerns about the disruptions to visitors and sharp drop in revenues, asked for emergency measures to restore the park.

Asked to give a background to the flooding, I made the following points and recommendations which I have supplemented with photos:

Asked to give a background to the flooding, I made the following points and recommendations which I have supplemented with photos:

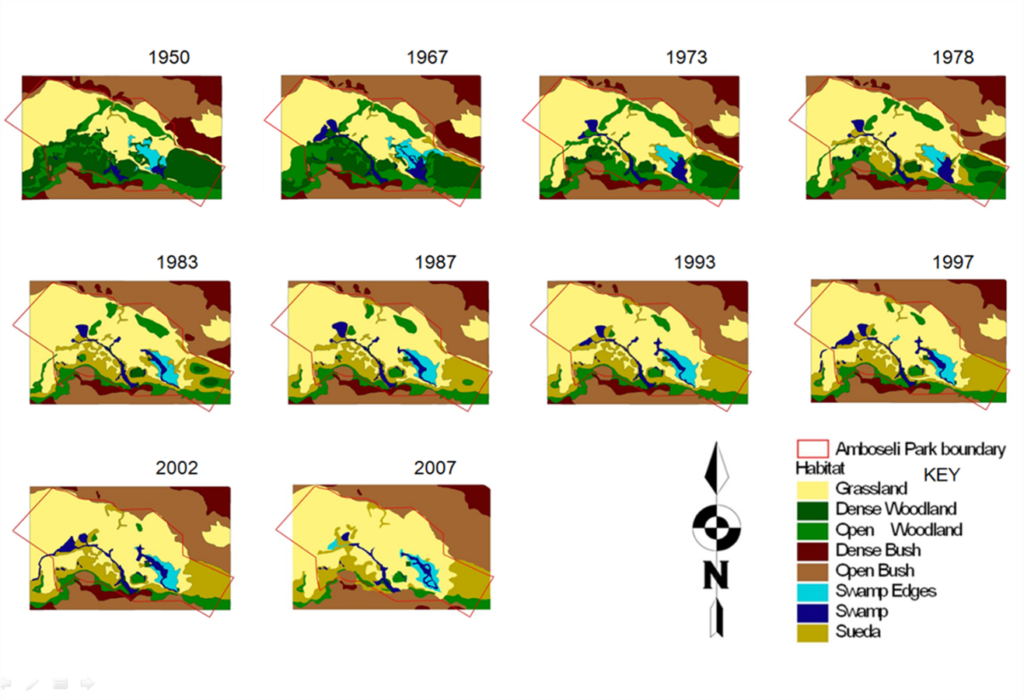

- Until 1992 the basin didn’t flood as it now does. The extensive woodlands and shrub cover arrested and contained the heaviest rainfall in small isolated pans.

- The loss of vegetation cover, coupled with extensive erosion from the higher elevations north and south of the basin, has caused the excessive inflow of water channeled into Longinye Swamp and out the far end across the central basin.

- The erosion is due to the permanent settlement and heavy erosion around Amboseli. The extensive flooding began in 1992 after migratory livestock herders set up permanent homes. The heavy permanent grazing caused a loss of ground cover and heavy erosional runoff flooding into the basin. The erosion channels caused by the incoming floods rushing into Longinye Swamp during the rains can be seen in the photo below

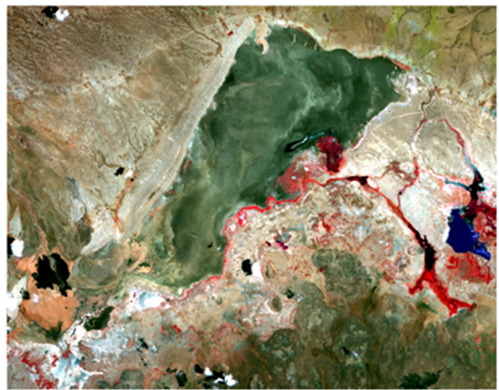

The clearest evidence of the flood waters originating off the heavily eroded lands around the park is captured in the satellite image below taken at the height of the floods.

The clearest evidence of the flood waters originating off the heavily eroded lands around the park is captured in the satellite image below taken at the height of the floods.

The flood waters are red-brown, the color of soils surrounding basin, rather than white soils of the basin and the flood pans filled by internal rainfall.

Two troughs stretching across the basin and visible from satellite imagery (below) drained Longinye Swamps into Lake Amboseli during historical periods of high rainfall. These channels have silted up over the decades.

Two troughs stretching across the basin and visible from satellite imagery (below) drained Longinye Swamps into Lake Amboseli during historical periods of high rainfall. These channels have silted up over the decades.

- The drainage troughs can be desilted to carry excess future flooding into Lake Amboseli. The survey and works should be completed before the next rains to avoid another tourist closure.

- In the meantime, I landed at the airstrip before the meeting to show it is fully usable and accessible to four-wheel-drive traffic. The airstrip should be reopened immediately to avoid further tourist disruptions.

- As a short-term measure can be taken to dump and level marram on the five kilometers or so of the main airstrip access and viewing roads. The roads, deflated by years of grading without recapping with marram to keep them raised above surface level, have become ribbon channels in many places.

- In the longer term, a range-land restoration program to combat erosion and restore pasture on the surrounding Ololorashi-Ogulului Group Ranch is underway. The program, funded by the Dutch NGO, Justdiggit through the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust and the African Conservation Centre, should reduce the erosional runoff into the basin in due course.

- One proviso of flood abatement that may need to be considered is whether to retain the enough seasonal flood waters to maintain the great attraction the thousands of flamingoes and water birds have become to the park.

The way forward

The way forward

- The meeting agreed that KWS would move ahead immediately to open the airstrip and repair the access roads and main viewing circuits in the central park.

- The lodge representative agreed to provide stop-gap funding if needed.

- KWS, working in collaboration with the lodges and ACP, will conduct a topographic survey to determine the desilting levels needed to channel the Longinye Swamp excess flooding into Lake Amboseli.

- The meeting was a positive step in engaging the tourism industry and conservation organizations in KWS’s planning and management of the park. The meeting should meet again within a month to review progress and become a permanent joint committee working for the future of Amboseli National Park and the larger ecosystem.

An analysis of livestock price fluctuations with droughts in eastern Kajiado

An analysis of livestock price fluctuations with droughts in eastern Kajiado

The livestock market in eastern Kajiado has steadily recovered after the near collapse in 2009 owing to the debilitating drought that led to losses of cattle, sheep, goats and donkeys.

The livestock market in eastern Kajiado has steadily recovered after the near collapse in 2009 owing to the debilitating drought that led to losses of cattle, sheep, goats and donkeys.

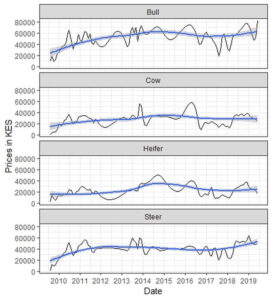

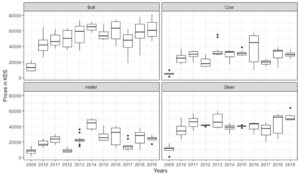

Prices fell below 1,000 Kenya shillings for a bull too weak to walk and surged to 90,000 Kenya shillings with the drought breaks (Figure 1). Amboseli Conservation Program monitors livestock market prices on a monthly basis and is in the process of modelling economic losses due to droughts and the gains when herders sell off their livestock early enough before periods of extreme forage shortfall.

A calibration of livestock prices based on monthly data collected in the ecosystem from 2009 to 2019 shows that the average prices for bulls in 2009 were in the red (Figure 2) falling 80.1 percent below the maximum expected market price.

A calibration of livestock prices based on monthly data collected in the ecosystem from 2009 to 2019 shows that the average prices for bulls in 2009 were in the red (Figure 2) falling 80.1 percent below the maximum expected market price.

The market recovered steadily up to 2014 with arrival of widespread rainfall and oscillated with seasonality thereafter.

The early warning model can guide herders on when to sell off their livestock based on forage conditions and market forces, while estimating economic losses due to extreme drought.

The early warning model can guide herders on when to sell off their livestock based on forage conditions and market forces, while estimating economic losses due to extreme drought.

The subdivision of Ogulului Group Ranch: Does it spell doom for Amboseli’s wildlife?

The subdivision of Ogulului Group Ranch: Does it spell doom for Amboseli’s wildlife?

Ololorashi-Ogulului Group Ranch (OOGR), which surrounds Amboseli National Park, supports most of its migratory wildlife in the wet season. The ranch has recently begun subdividing the 330,000-acre ranch among its 5,000 members.

Conservationists are deeply concerned, fearing there is no place for wildlife on small subdivided lands, and with good reason: ten years ago, Rosemary Groom and I called attention to the steep decline in wildlife following the subdivision and degradation of the Kaputei group ranches north of Amboseli [1].

Today the once large seasonal migrations of wildebeest and zebra have vanished. Wildlife in Amboseli faces a similar fate if OOGR ranch carves up and settles the migratory routes across the ecosystem.

Parks are no panacea for conserving wildlife; numbers are declining in lockstep with losses in the surrounding lands and across Kenya as a whole [2].

How real is the threat of OOGR to the future of Amboseli’s wildlife and the national park?

The subdivision of the Amboseli ecosystem into Kaputei-like settlements reflects a far large threat to Kenya’s rangelands. The Ministry of Lands in 2019 declared that all community lands are open to adjudication into private allotments, opening the floodgates to the fragmentation and degradation of Kenya’s savannas and pastoral livelihoods.

The push for the subdivision of OOGR has been building for two decades. The pressure stems partly from a fear of land grabs, partly from the economic and social transition from subsistence pastoralism to settled livelihoods. The push has been held back by the group ranch and political leaders cautioning members about the dangers of carving up the open rangelands into plots too small to support a family, and the dangers of outsiders and land speculators buying up the pastoral lands.

The leaders point to the fate of Kimana Group Ranch adjacent to Amboseli as a warning. Following subdivision, most of the land was sold to settlers and farmers.

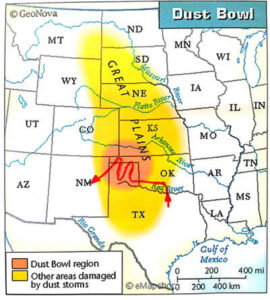

I recently visited the American prairies, which were carved up into similar small parcels in the 1920s, to gauge the risks of subdividing Kenya rangelands. (See A visit to the American Dust Bowl 80 years on: Lessons for the African Savannas). The visit convinced me that family herders and farmers in the African savannas face a similar fate unless the allocation of title deeds takes account of the health of the land.

To avoid Amboseli and Kenya’s rangelands going the Kaputei and Dust Bowl way, OOGR must ensure its members can secure title to their lands without destroying them for livestock and wildlife alike. In short, OOGR is a testcase for future of Kenya’s pastoral lands.

Caught between the pressures for subdivision and concerns over land degradation and sales to outsiders, OOGR has held lengthy discussions over the years to find a balance between land security, settlement, viable family herds and wildlife conservation. A draft plan was presented to wildlife conservation organizations in 2014, soliciting inputs. The final plan, a 100-page document prepared by consultants, was completed early in 2019, approved by Kajiado County and released at a workshop which included the Kenya Wildlife Service and conservation organizations.

In summary, the 330,000 acre OOGR group ranch is being subdivided among its members into four zones: 1) ten village service areas where each member is allocated a quarter acre for settlement and provided social services; 2) a pastoral grazing areas where each member is allocated 21 acres; 3) four wildlife conservation areas to allow free wildlife movements and within which each member is allocated a nominal 8 acres, and 4) farming allocations in the Namelok area east of Amboseli National Park which have already been allocated and developed.

Permanent settlements and fencing will be prohibited in the pastoral and wildlife areas in order to sustain seasonally mobile livestock keeping under the existing OOGR grazing plan. A caveat on each title deed will bar permanent settlement, fencing and land sales for 99 years.

The chairman of OOGR, Daniel Leturesh, stated in his presentation to conservation NGOs that Ogulului intends to set up a trust to manage pastoral and wildlife areas and invited discussion on how it might operate and the role the NGOs might play. Both Kajiado County and national government planners consider that the OOGR might offer a way to grant individual title deeds to Kenya’s extensive rangelands yet keep them open for pastoralism and wildlife.

On 7th August the Amboseli Ecosystem Trust (which represents all seven group ranches in the ecosystem) presented the OOGR plan to conservation organizations working in the region. The workshop was attended by twenty-five conservation organizations and the Kenya Wildlife Service. Jackson Mwato, coordinator of AET, presented the background to the plan.

I was asked to cover the ecological considerations drawing on ACP’s fifty years of monitoring data. The findings showed wildlife migrants moving wildly across the ecosystem in in response to erratic rainfall. The dry season concentration area and wet season dispersal of the wildlife and livestock migrants define the Minimum Viable Conservation (MVCA), which the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 is using to define the ecosystem.

So far, the MVCA has remained open to livestock and wildlife movements and the population sizes of the migratory species, including zebra, wildebeest and elephants, which hare determined largely by the forage availability in the woodlands and swamps of Amboseli National Park, have been sustained.

The main goals of the OOGR plan are to ensure community development, pastoralism and wildlife populations. Provided it does ensure the continued seasonal mobility of wildlife and livestock populations, it can achieve the three objectives. Key to its success is a rotational livestock grazing plan designed and adopted by OOGR. The grazing plan aims to restore pasture production and reverse land degradation. If maintained, individual land holdings need not impair wildlife and livestock movements. If, however, , land titles lead to permanent settlement on each plot, the rangeland will deteriorate rapidly and cause a rapid decline in wildlife, family herds and the pastoral economy.

The conservation organizations issued a statement at the end of the meeting on 7th August recognizing the right of the landowners to decide the use of their land and taking a neutral position on the plan, except to express their commitment to conserving Amboseli as a unique wildlife area of national and international significance.

The OOGR subdivision and zoning plan met resistance from a political faction of the group ranch, claiming there has been insufficient consultation. The protestors burned down the International Fund for Animal Welfare’s rangers camp and tourist facilities, then attempted to burn down Nongotiak Centre. The warriors involved were thwarted by the community and arrested by police. Following intensive negotiations and community meetings, the rival factions have since reached agreement on how to move ahead.

Whether the plan will strike a balance between granting individual land titles and sustaining pastoral herds and wildlife hinges on winning the agreement and compliance of its members on the type of governance to replace the dissolution of group ranches. In anticipation of subdivision, ACP and ACC have been in discussion with the OOGR leaders and AET over the last two years. The trust now assumes great urgency.

The rapidity of OOGR’s subdivision calls for urgent action to ensure a lands trust does replace the group ranch before its dissolution. On a positive note, the Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 was vetted and adopted on 11th December by all group ranches, KWS and conservation organizations working in the ecosystem. (See Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 ratified and adopted, 7 January 2020). The adoption of AEMP signals a strong commitment of all parties to sustaining the vitality of Amboseli’s wildlife as an integral part of the region’s development plans.

OOGR has signaled its intention to explore the prospects of a land trust under the umbrella of AET. ACC and ACP are also consulting other conservation organizations, the Rangeland Association of Kenya and government agencies on the prospects of land trusts serving the interests of pastoral communities across the rangelands in order to avoid the fragmentation and degradation of Kenya’s rangelands.

References

[1] David Western, Rosemary Groom, and Jeffrey Worden, “The Impact of Subdivision and Sedentarization of Pastoral Lands on Wildlife in an African Savanna Ecosystem,” Biological Conservation 142, no. 11 (2009): 2538–46; Rosemary J Groom and David Western, “Impact of Land Subdivision and Sedentarization on Wildlife in Kenya’s Southern Rangelands,” Rangeland Ecology & Management 66, no. 1 (2013): 1–9.

[2] David Western, Samantha Russell, and Innes Cuthill, “The Status of Wildlife in Protected Areas Compared to Non-Protected Areas of Kenya,” PloS One 4, no. 7 (2009): e6140.

Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 ratified and adopted

Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 ratified and adopted

The Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan (AEMP) 2020-2030 was ratified and adopted at a workshop in Machakos on 11 December after many meetings of the Project Implementation Committee, partner organizations and community members over the last eighteen months.

The plan replaces the first AEMP covering the period 2008 to 2018. In the next few weeks the new plan is expected to be formally adopted by county and government agencies and gazetted by the Attorney General. AEMP, the first of its kind to incorporate wildlife and natural resource management into a broader planning framework, lays out a framework for sustaining the land health of the rangelands throughout Kenya and beyond.

Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) prepared the main report on the Amboseli ecosystem undergirding AEMP 2020-2030. The following is a summary of AEMP 2020-2030 outline of the 151-page plan:

The Plan

The vision for the Amboseli Ecosystem: “To sustainably manage and utilize the ecosystem’s natural resources for community livelihood improvement”

The Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan is an integrated plan that outlines how different land uses and natural resources in the Amboseli Ecosystem will be managed for the greater good of all stakeholders. The renewal of AEMP 2008-2018 for a further 10 years is a clear indication that the stakeholders, who include landowners, KWS, NGOs, the tourism industry and researchers, are committed to an ecologically viable Amboseli Ecosystem.

The plan takes a broad multi-sectoral view of all the natural resources in the ecosystem against different land uses and how these interact with one another and, ultimately, how they co-exist within the ecosystem.

The Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 is the second AEMP after the lapse of the first ten-year AEMP 2008-2018. This AEMP incorporates lessons learned during the implementation of the first AEMP.

The Amboseli Ecosystem Management Plan 2020-2030 is the second AEMP after the lapse of the first ten-year AEMP 2008-2018. This AEMP incorporates lessons learned during the implementation of the first AEMP.

It is a product of broad-based consultations among diverse stakeholders beginning with government entities of national and county levels, the group ranches, NGOs, Hoteliers and Tour Operators.

The stakeholders and especially the CPT who were the Plan Implementation Committee (PIC) members of the first AEMP, brought up diverse views, expertise and a plan foundation report describing biophysical and social components necessary to achieve the desired future conditions for community livelihoods, ecology, tourism, and institutions and governance systems in the Amboseli ecosystem. The report set out the strategic principles and socioecological relationships, and rationale for development of the new AEMP.

The plan foundation report was an update of a previous report that was used to develop the AEMP 2008-2018. It pinpointed threats to the productivity and viability of the Amboseli ecosystem and national park, the main threats, such as increasing farming, settlement, fencing, subdivision, water extraction from rivers and swamps, the loss of seasonal grazing grounds and drought refuges for livestock and wildlife, and heavy grazing pressure which was reducing the productivity and resilience of the ecosystem.

The threats also included bush meat poaching, a breakdown of migrations and compression of wildlife (elephants especially) into Amboseli National Park, and the resulting loss of habitat and species diversity.

It further recommended specific actions to combat the threats and the creation of Amboseli Ecosystem Trust (AET) to oversee the implementation of the plan. The updated report is the foundation of the new AEMP, and Amboseli ecosystem stakeholders built on this foundation to develop the new plan.

The AEMP 2020-2030 has a wide scope which includes livestock development, rangeland and water management, agriculture, permanent settlements, and urbanization and new enterprises. It also addresses the changes over the last decade and the threats to the ecosystem.

These threats include land subdivision, agricultural expansion, water extraction for farming and other commercial activities, loss of seasonal pastures, and the growing impact of grazers and browsers on habitat, species diversity, and plant production and on livestock and wildlife populations.

As a follow up of the AEMP 2008-2018, the aim of which was to maintain habitat connectivity and safeguard the viability of the Amboseli migratory wildlife populations, the new AEMP strives to maintain and restore ecosystem integrity to safeguard Amboseli’s wildlife and community livelihoods based on the Minimum Viable Conservation Area.

The ecosystem plan also spells out the role of AET and partnering organizations in presiding over the plan implementation, and defines the central role of the Noonkotiak Resource Centre as the information and research hub of the ecosystem, coordinating ecosystem monitoring and planning, setting up an information database, tracking and adapting management plans and developing a visitor and cultural centre and education outreach program.

The AEMP 2020-2030 integrates the land use plans of the seven group ranches, Olgulului/Ololarashi, Mbirikani, Eselenkei, Kuku, Rombo, former Kimana group ranch and Amboseli National Park. Group ranch land-use plans have been developed to minimize land use conflicts and enhance community livelihoods.

The plans consider facilitating conservation of viable wildlife populations at the ecosystem level by planning for wildlife migratory routes and critical refuges. They also include restoring degraded lands through “Olopololi” (grass banks), resting and rotation of pasture use, soil erosion control measures and establishment of wildlife conservancies.

A visit to the American Dust Bowl 80 years on: lessons for the African savannas

A visit to the American Dust Bowl 80 years on: lessons for the African savannas

I wrote a couple of articles in Kenya’s Nation newspaper during the 2000 millennium drought warning of worse times to come unless we took steps to arrest the impact of land subdivision, settlement and farms on the pastoral and wildlife lands of the East African savannas.

I wrote a couple of articles in Kenya’s Nation newspaper during the 2000 millennium drought warning of worse times to come unless we took steps to arrest the impact of land subdivision, settlement and farms on the pastoral and wildlife lands of the East African savannas.

In the coming years as the degradation worsened and droughts intensified, I pointed to the lessons we could learn from the tragedy of American Dust Bowl in the 1930s.

Timothy Egan’s The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl is a fine first-hand account told by the survivors. The Great Plains—the American Serengeti as it has been called–had for millennia been home to millions of bison, elk and prong horn antelope and the Comanche, Arapaho and other tribes who hunted them.

The high plains in the southwest were the last of the American prairies to be carved up and handed out to homesteaders in late 19th century. Following the extermination of the bison and incarceration of the plains Indians in reservations, homesteaders lured by cheap land, ready bank credits and a quick fortune from the booming wheat and cattle markets arrived in the tens of thousands to farm the prairies.

The story goes that cattlemen and farmers—sod-busters as they were called—settled the plains in a wet period, overused the land and destroyed the grass cover binding the fragile soils.

The wheat and cattle boom deflated with the return of dry years and plunging crop and beef markets. Farmers plowed more land to cover their loses and by 1934 the barren land began to lift, creating huge dusters, black blizzards and drifting sands. Over 2 million people were displaced in a humanitarian disaster that helped topple President Herbert Hoover and usher in F D Roosevelt who mobilized thousands of young men to plant trees and stabilize the prairie soils.

What had happened to the degraded land since the Dust Bowl era? What became of the family farmers, herders and wildlife? And what lessons did the prairie Dust Bowl offer the African savannas?

This was a story worth pursuing, yet oddly I could find little about the Dust Bowl or the settlers after the tragedy. In March of 2019 I paid a visit to the Texas-Oklahoma panhandle at the epicenter of the disaster to find out. My drive took me through the worst hit of the Dust Bowl regions—Arnett, Shattuck, Higgins, Glazier, Canadian, Miami, Pampa, Amarillo, Channing, Dalhart, Boise City, Clayton and Springer.

I start out from Norman south of Oklahoma City and travelled along route 40 where the land turns drier, the grasslands sparser and the ground barren. In Clinton where I stop off to refuel, the town, like others along the route, is shedding population and businesses like autumn leaves and homes are decaying like inner-city ghettos.

Half the stores and businesses in Elk City, where I haul in for coffee, are shuttered. A solitary visitor drops by in the half hour, I spend chatting to the owner. Sayr, where I turn north onto 283, is ghostly quiet. The stores on the main street are derelict. All but two gas stations are boarded up for lack of custom. At the historical museum, General Custer is more celebrated than the homesteaders who survived the Dust Bowl tragedy and the first settlers, the Indians who occupied the Great Plains for millennia beforehand.

On the drive through Black Kettle National Grassland reserve, I pass through areas heavily battered and degraded in the 1930s. Dozens of farms are abandoned, homes are crumbling, and fields are being recolonized by bunch grass and scrub too coarse and dry to see a cow through winter.

The small holdings have been bought out by large farming conglomerates which have defeated the hostile climate by drilling deep down to the Ogallala Aquifer and using the energy of fossil fuels pumped from yet deeper into the earth to power huge articulating irrigation booms which water circular fields of cattle fodder, maize, wheat and cotton.

Oil rigs by the hundreds dot the farmlands and supplement corporate incomes from corn and beef trucked to distant American families. Despite its name, Black Kettle Grassland has restored little natural grassland. Large irrigated farms blanket the landscape and dwarf the national grasslands bought up by Roosevelt during the New Deal to relieve destitute farmers.

Up the road from Channing hay fields give way to corn as I approach Dalhart. Dalhart, sitting at 4,600 feet above sea level, averages less than 14” of rain. Unlike the tropics where rainfall increases with altitude, the cold and wind of the high plains shorten the growing season. It takes deep corporate pockets and oil from dozens of rigs to capitalize the heavy-duty tractors, combines and fertilizers needed to grow a bounty of corn and wheat in an area where American family farmers failed to make a living in the Dust Bowl days.

I drive to Boise where only a few scattered tracts hint at the once endless prairies among the large commercial farms. I spot only two herds of prong horned antelope in the remnant grasslands where tens of thousands once roamed. My next stop, Boise City, is fast becoming a ghost town where hospitals, churches, meeting halls and whole streets are abandoned and shuttered. The town is graveyards of old cars, truck, tractors, combine harvesters and metal grain silos.

Like so many dying towns in the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandle, human graveyards are filling up as the towns empty out. How sad and morbid driving past the derelict homes of families who once worked the land, loved, married, and raised children here, only to watch their way of life vanish and their youngsters move to the cities.

I check into the Kokopelli Lodge in Clayton for the night after driving through intensively irrigated flat and featureless land with not a tree in sight, except where some homesteader planted a few as windbreaks around a small clapboard cabin. Today the houses are few and far between and sizeable, used by managers who tend the farms and drive the plant. With every aspect of farm production, harvesting, marketing and distribution closely monitored and analyzed by GPS devices and computer programs, farming today is technocracy rather than husbandry.

Nearing Clayton, I turn off the highway to check out a vast feedlot of some 10,000 cattle packed belly to belly in 50 acres of paddock. “This is the dinner you eat,” reads the sign at the entrance to the factory farm. The stench is so strong from the slop of mud and dung that I stop for a quick snapshot and rush on for fresh air. If the smell was served up with every slab of beef and hamburger in homes and restaurants, America would banish factory farms.

Clayton, unlike the other victims of depopulation on the High Plains, shows signs of renewal among the shuttered buildings as visitors keen to get a feel of the pioneer days stop by overnight.

The drive to Springer climbs steadily to 5,800’. Extensive grasslands stretch to a low ridge of hills to the north. The scene resembles Serengeti looking across to the Nabi Hills, the more so for a herd of pronghorn antelope grazing the shortgrass plains. The plains are the epitome of the abandoned dust bowl scenes, minus the wind-swept sands.

Widely scattered abandoned homes with a few spindly trees and crumbling windmills dot the high plains. Life must have been a lonely and spartan for the Dust Bowl survivors who hung on after the destitute families drifted away. The ranches nowadays run to thousands of acres with barely a cow and never a herder in sight. I don’t see a single person on the 60-mile drive to Springer at the end of my Dust Bowl tour with much to reflect on.

The damage caused by the spread of European colonialism around the world and across the US prompted President Roosevelt to convene the Conference of Governors on the Conservation of Natural Resources in 1908. In his opening address he asked, “what will happen when our forests are gone, when the coal, the iron, the oil and the gas are exhausted, when the soils shall have been still further impoverished…We began with soils of unexampled fertility land, and we have so impoverished them by injudicious use and failing to check erosion that their crop-producing power is diminishing instead of increasing.”

Yet the very next year, in 1909, a Soil Bureau’s statement read: “The soil is the one indestructible, immutable asset that the national possess. It is the one resource that cannot be exhausted; that cannot be used up”. This view was contested by experts, including High Hammond Bennett, who warned of the devastation homesteaders and farmers would cause on the high plains, and with good reason.

The grasslands rise from 2,000’ to over 6,000’, have sparse sporadic rainfall, periodic droughts, searing heat and hurricanes in summer and bitter cold spells and blizzards in winter. The plains are treeless and parched dry most of the year with little drainage or surface water. Most rains fall in spring and summer when high temperatures and wind reduce infiltration and water-use efficiency.

The plains in the heyday of the bison herds were dominated by grama-buffalo grass, wire grass, bluestem bunch grass and sand grass-sand sage. The soils are largely loess, remnants of the windblown soils of the post-glacial period held in place by an overburden of thin organic soils bound by plant roots. Beneath the loess is a minerally-leached calcareous hard pan.

The roots trapped the moisture and held the soils in place during the heavy seasonal grazing by migratory buffalo herds. The desiccation of plant and water would have given the grasses a long rest period after the bison retreated to their winter grounds.

Despite the warnings, the federal government was so intent on exploiting the last of the open prairie lands after the army defeated the Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapahoe that it granted 320 acres of land to settlers under the Enlarged Homelands Act of 1909.

Ignoring the marginal conditions, hostile climate and vulnerability of the high plains to overuse, settlements in the Llano Estacado in eastern New Mexico and northwestern Texas doubled between 1900 and 1920 and accelerated again in the 1920s with a rise in cereal prices on the world market and a run of good rainfall years. Hannah Holleman in her recent book, Dust Bowls of Empire, agrees with Donald Worcester’s classical account in Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s: the immediate causes of the Great Plains disaster were market forces, tenant farmers replaced by mechanization, overextended credit, injudicious land clearing and farm practices, drought and the natural vulnerability of the high plains—the ultimate forces capitalism and agro-industrial farming.

The phases of agricultural intensification are still detectable in the dilapidated homesteader shacks, in the farmhouses of wealthier ranchers and farmers who bought them out, and in the industrial farms with their giant pivot irrigation booms watering fertile fields of hay and corn. Industrial farming favors big corporations able to invest in heavy equipment and ride out lean years.

The phases of agricultural intensification are still detectable in the dilapidated homesteader shacks, in the farmhouses of wealthier ranchers and farmers who bought them out, and in the industrial farms with their giant pivot irrigation booms watering fertile fields of hay and corn. Industrial farming favors big corporations able to invest in heavy equipment and ride out lean years.

I doubt they would make a go of it either without the extraction of voluminous flows of water from the deep aquifers made possible by cheap oil and farm subsidies paid for by the American taxpayer.

The towns in the Dust Bowl region grew with farm production on the high plains, only to fall on hard times when agrobusiness moved in and cut the labor force to the core. Today the towns no longer have the population or tax base to keep schools, libraries, and fire stations open, or maintain the roads.

The remaining residents are aging and struggling to hold on. Their homes are falling into disrepair, barely distinguishable from abandoned houses. The dying towns are graveyards of rusting farm machinery and acres of abandoned cars.

What of the future?

The Dust Bowl 80 years on is carpeted over with greenery, insulating the earth from the wind-blown erosion. Large areas no longer farmed have reverted to grass and shrub cover reminiscent of the bison prairies though no native in composition.

Dust storms may recur in extreme years, and have a few times since, but only locally and with nothing like the severity of the Dust Bowl era than blew away 75 percent of the topsoil.

The Dust Bowl was a product of its time, a conflation of human hubris, ignorance, and extreme drought. The land parcels were too small for family farmers to make a living, let alone better lives. Farm technology was a case of too much horsepower for the good of the land in the hands of farmers who lacked familiarity with the earth.

The Dust Bowl was a product of its time, a conflation of human hubris, ignorance, and extreme drought. The land parcels were too small for family farmers to make a living, let alone better lives. Farm technology was a case of too much horsepower for the good of the land in the hands of farmers who lacked familiarity with the earth.

Ironically, it took yet more technology, energy and capital to make the land productive. Agro-industrial farming today has turned a disaster zone into a breadbasket and feed lot for urban America.

I read Donald Worcester’s classic Dust Bowl after my trip to the Oklahoma-Texas Panhandle and agreed with his conclusions after revisiting the area where he grew up:

“Capital-intensive agribusiness had transformed the scene; deep wells in the aquifer, intensive irrigation, the use of artificial pesticides and fertilizers, and giant harvesters were creating immense crops year after year whether it rained or not”. According to the farmers he interviewed, technology had provided the perfect answer to old troubles.

“Capital-intensive agribusiness had transformed the scene; deep wells in the aquifer, intensive irrigation, the use of artificial pesticides and fertilizers, and giant harvesters were creating immense crops year after year whether it rained or not”. According to the farmers he interviewed, technology had provided the perfect answer to old troubles.

The bad old days will not return, they insist. In Worcester’s view, by contrast, the American capitalist high-tech farmers had learned nothing. They were continuing to work in an unstainable way, devoting far cheaper subsidized energy to growing food than the energy could give back to its ultimate consumer”.

It seems to me the corporate farmers are also a product of their time, sustainable only as long the oil, aquifers and government subsidies last, the present climatic conditions hold, Americans continue to eat 50 pounds or more of beef each year, and are willing to tolerate the cost of leached fertilizers and pesticides into the landscape and rivers and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

It seems to me the corporate farmers are also a product of their time, sustainable only as long the oil, aquifers and government subsidies last, the present climatic conditions hold, Americans continue to eat 50 pounds or more of beef each year, and are willing to tolerate the cost of leached fertilizers and pesticides into the landscape and rivers and greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

When subsidies, diets and climate changes and aquifer sink to uneconomic levels, the high plains will change once more. The future is already emerging in new wind and solar farms and with the new nature sensibilities that attract visitors to enjoy the vastness of the Great Plains and its history.

Are there lessons from the Dust Bowl for the savannas now being subdivided, privatized, and settled? I think so, in several ways. Perhaps the most important is to recognize that land as a commodity rather than the foundation of a communal way of life that has sustained East African pastoralists for generations is liable to the vicissitudes of market forces and short-term gains. The savannas are in the process of becoming market producers of beef and grain rather than family sustenance and welfare.

Are there lessons from the Dust Bowl for the savannas now being subdivided, privatized, and settled? I think so, in several ways. Perhaps the most important is to recognize that land as a commodity rather than the foundation of a communal way of life that has sustained East African pastoralists for generations is liable to the vicissitudes of market forces and short-term gains. The savannas are in the process of becoming market producers of beef and grain rather than family sustenance and welfare.

As in the Dust Bowl, the private allotments are far too small to support a family. Cattle barons land speculators are eying the fallout of subdivision and degradation. The same exodus of dispossessed families is underway.

It will take the resident families banding together as producer associations and land trusts to use the land sustainably for the benefit of its resident members. Even then, a large-scale emigration from the land to the cities is inevitable in the coming decades as the population grows larger than the land can support–and the younger generation seeks new opportunities.

Education is key to providing a passport to opportunities elsewhere. There is also an urgent need to restore the rotational use of grasslands that sustained pastoral livestock and wildlife for millennia in the East African savannas and to embark on a restoration program for the degraded lands, much as Roosevelt did in the Dust Bowl era.

Tracking pasture conditions and predicting droughts in the Amboseli ecosystem

Tracking pasture conditions and predicting droughts in the Amboseli ecosystem

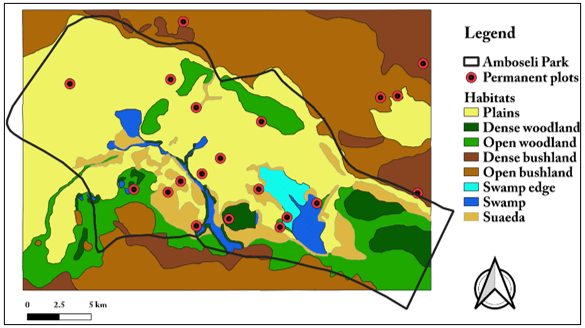

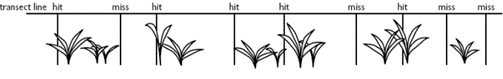

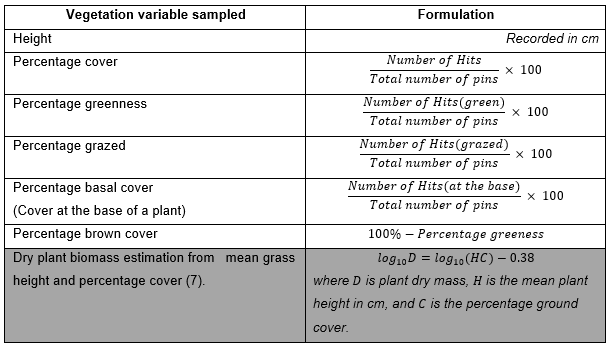

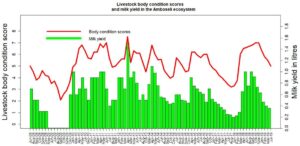

Amboseli Conservation Program has been tracking range-land conditions in the Amboseli region since 1976. The tracking measures plant biomass, greenness and grazing pressure in 20 permanent plots each month in the 700 square kilometer area in and around the Amboseli Basin used heavily by livestock and wildlife in the dry season. The methods used and the results of the long-term monitoring have been published in (Western et al., 2015)

We have now developed a simplified method of graphically presenting the range-land tracking data to provide group ranch and grazing committees an early warning system indicating the severity of pasture shortage for each year and month.

We have now developed a simplified method of graphically presenting the range-land tracking data to provide group ranch and grazing committees an early warning system indicating the severity of pasture shortage for each year and month.

The method uses grazing pressure on a scale of 0 to 100 as a measure of pasture availability. Zero grazing occurs after good rains and low grazing pressure. To simply the index we use an arrow to indicate the severity of pasture conditions. The arrow in the green range indicates less than a third of the pasture has been grazed down, amber up to two thirds and red severely grazed.

The Illustration 1 below shows the severity of each year from 1976 to 2018. In 1976 pasture was severely grazed down, causing a 50 percent loss of cattle. Grazing pressure was low in the following five years and pastures recovered.

From 1982 onward the grazing pressure increases steadily with shorter intervals of recovery until 2009, the worst year on record when the needle indicates an average of 73 percent grazing pressure. In 2009 over 70 percent of livestock, 50 percent of sheep and goats and large numbers of wildebeest, zebra and elephants died of starvation. From 2010 onward the recovery is far poorer and shorter lived than in earlier years due to heavy grazing pressure.

By 2017 the grazing pressure needle moved into the second highest level recorded. 2018 would have been as severe as 2009 had the drought not been broken by extremely heavy rains. Despite the heavy rains, pasture conditions are shaping up to be very severe in 2019.

Illustration 2 shows the monthly pasture conditions for 2019 for Amboseli, Eselenkei, Mbirikani and Kimana group ranches. The needle has already moved into the red zone due to poor short rains and heavy grazing pressure.

Illustration 2 shows the monthly pasture conditions for 2019 for Amboseli, Eselenkei, Mbirikani and Kimana group ranches. The needle has already moved into the red zone due to poor short rains and heavy grazing pressure.

In the coming dry season Amboseli and all group ranches in the region will experience severe pasture conditions. Unless the region has nonseasonal rains before late September and the pressure relieved by the sale of livestock or outward migration, substantial mortality is likely to occur by October.

We will be developing and posting tracking details on livestock body condition, milk yields and market prices over the coming month to improve ACP’s range-land monitoring and projections of the seasonal outlook.

We will be developing and posting tracking details on livestock body condition, milk yields and market prices over the coming month to improve ACP’s range-land monitoring and projections of the seasonal outlook.

Illustration 3 gives a preview of livestock condition and milk production adding weight to the severe outlook for the 2019 long dry season and an early warning of the need for early action to prevent heavy economic losses.

Kenya’s wildlife: A success story still in the making?

Kenya’s wildlife: A success story still in the making?

In 1969 Dr. Western gave a public talk at the National Museums of Kenya urging the need to engage communities and general public in wildlife conservation.

In 1969 Dr. Western gave a public talk at the National Museums of Kenya urging the need to engage communities and general public in wildlife conservation.

Over 50 years later he reviewed the strides Kenya has made yet the continuing failures to halt wildlife declines.

In his talk he reviews how Kenya turn the tide and make its wildlife conservation a real success story.

ACP trains Department of Remote Sensing and Resource Survey (DRSRS) team on open source tools

ACP trains Department of Remote Sensing and Resource Survey (DRSRS) team on open source tools

As commercial software become increasingly expensive, many government institutions across Africawide are turning to opensource applications for data management and analysis. The adoption of opensource technology, raises the challenge of technical skills needed to customize the software to fit organizations’ data needs.

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) has over the years developed opensource technologies for application to various research needs (download paper here). In March 2019 the ACP team in collaboration with the South-Rift Association of Land Owners (SORALO) and the Uaso Ngiro Baboon Project (UNBP) trained the Department of Regional Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS) in the applications of these software tools.

The Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) has over the years developed opensource technologies for application to various research needs (download paper here). In March 2019 the ACP team in collaboration with the South-Rift Association of Land Owners (SORALO) and the Uaso Ngiro Baboon Project (UNBP) trained the Department of Regional Surveys and Remote Sensing (DRSRS) in the applications of these software tools.

The training sessions covered data management in R, Rstudio, statistical significance testing, mapping and estimations of animal populations and distributions from aerial survey data conducted in Kajiado County, southern Kenya. The training took place at African Conservation Centre offices in Karen.

The tools, which integrate data entry, processing and mapping, can be easily adapted to processing countrywide species population estimates from aerial surveys conducted by DRSRS. Historical counts can also be rapidly processed for spatial trends and subsequent policy advice.

Looking ahead, ACP will expand the training for other conservation organizations to include web applications in R shiny for data analysis, management and mapping. The application requires users to have basic computer skills hence allowing non-technical personnel to interact with and process available institutional data.

Variability and Change in Maasai Views of Wildlife and the Implications for Conservation

Variability and Change in Maasai Views of Wildlife and the Implications for Conservation

Surveys conducted across sections of the pastoral Maasai of Kenya show a wide variety of values for wildlife, ranging from utility and medicinal uses to environmental indicators, commerce, and tourism.

Surveys conducted across sections of the pastoral Maasai of Kenya show a wide variety of values for wildlife, ranging from utility and medicinal uses to environmental indicators, commerce, and tourism.

Attitudes toward wildlife are highly variable, depending on perceived threats and uses.

Large carnivores and herbivores pose the greatest threats to people, livestock, and crops, but also have many positive values. Attitudes vary with gender, age, education, and land holding, but most of all with the source of livelihood and location, which bears on relative abundance of useful and threatening species.

Traditional pastoral practices and cultural views that accommodated coexistence between livestock and wildlife are dwindling and being replaced by new values and sensibilities as pastoral practices give way to new livelihoods, lifestyles, and aspirations.

Human-wildlife conflict has grown with the transition from mobile pastoralism to sedentary livelihoods. Unless the new values offset the loss of traditional values, wildlife will continue to decline.

New wildlife-based livelihoods show that continued coexistence is possible despite the changes underway.

Full article available at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-019-0065-8

Spatial and social ecological dynamics of human wildlife interactions in Amboseli Kenya

Spatial and social ecological dynamics of human wildlife interactions in Amboseli Kenya

In March, Victor Mose gave a presentation on Spatial and social ecological dynamics of human wildlife interactions at the Institute of Research and Development (IRD) stand at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-4) in Nairobi.

In March, Victor Mose gave a presentation on Spatial and social ecological dynamics of human wildlife interactions at the Institute of Research and Development (IRD) stand at the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-4) in Nairobi.

His talk highlighted the need to factor in the social aspects such as human attitudes towards wildlife in modelling their interactions.

The presentation is part of ACP’s multidisciplinary approach to understanding the drivers of human wildlife interactions and implication for species conservation and coexistence.

The power of visualizing spatial and temporal data in developing and testing ecological hypothesis

The power of visualizing spatial and temporal data in developing and testing ecological hypothesis

Using exploratory data analysis to visualize and test hypothesis is fast becoming a method of choice for many researchers working across disciplines.

Using exploratory data analysis to visualize and test hypothesis is fast becoming a method of choice for many researchers working across disciplines.

Data visualization allows team members to work together in building ideas about how ecological systems work. Victor Mose outlined the benefits of this approach at the third annual International Biometric Society (IBS)–Kenya chapter held at the Strathmore University in Nairobi.

He used the long-term Amboseli data to show how spatial exploratory data analysis can reduce complex ecological hypothesis to simple visual presentations with cross-cutting research applications.

The approach requires no prior knowledge about the data and can be rapidly applied to formulate and test hypothesis in visual form with wide applications.

Data collection platform for Resource Assessing upgraded

Data collection platform for Resource Assessing upgraded

Following the launch of a digital platform to collect animal and plant data by Amboseli Conservation Program (ACP) last year, the Resource Assessors (RAs) were due for advanced training in the use of digital platform.

This platform now includes livestock herd follows, milk production and market prices recording and general livestock value chain monitoring.

In the first week of September 2018, ACP trained all the RAs working in the Amboseli area on the upgraded tool during a two-day workshop at African Conservation Centre (ACC) offices in Karen, Nairobi.